We came across this interesting article by a Zimbabwean blog and decided to share with you. Do enjoy.

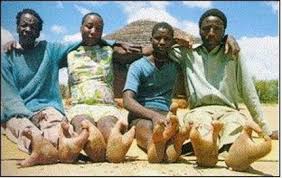

Urban legend has it that the Doma – referred to some as the Ostrich People of Zimbabwe – are all two-toed.

The truth is that this is a genetic condition that affects only a particular family.

One online source says “a substantial minority of this tribe has a condition known as ectrodactyly in which the middle three toes are absent and the two outer ones are turned in, resulting in the tribe being known as the ‘two-toed’ or ‘ostrich-footed’ tribe”.

Ectrodactyly is an autosomal dominant condition resulting from a single mutation on chromosome number seven. Those with the condition are not handicapped and are well integrated into the tribe. It was against this background – that the Doma folks are two-toed – that we set to learn about their lifestyles and how they cope with life having only two toes or two fingers. Some literature has even falsely attributed this deformity to being an adaptation to tree-climbing, which the authors claim is essential as the tribe derives its livelihood on hunting and gathering. Having led a largely nomadic life until their integration into “normal” society, the Doma people have slowly adapted to a settled subsistence farming life, though their farming methods are still primitive and laborious. Prior to settling down, the larger proportion of the Doma people lived in the mountains that border the mighty Zambezi River, where they survived mainly on hunting and gathering.

However, when hunting changed meaning to poaching as central Government sought to criminalise unauthorised killing of wild animals, the shifting legal terrain forced the Doma people to move from the mountains to settle in the surrounds of the Zambezi River, settling mainly in and around the basins of Mwazamutanda River, a tributary to the Zambezi. “It has been a long process but they have slowly understood the implications of them continuing to hunt and we always engage them from time to time, to show them the good side of a settled life and I think it is a situation we are winning,” explained Chief Chapoto, under whose chieftainship, most of the Doma people live.

Whilst Chief Chapoto might be content on the successes that his community has scored in integrating the Doma people, our first port of call when we went up Mwazamutanda, where most of them reside, told a different story.

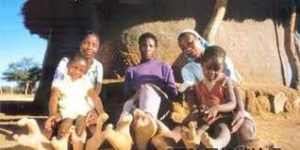

According to Charles Jabesi, our guide for the day, Stobart Chidongo, who is also known as Sauti in his community, is among the more enlightened of the Doma people.

But his family of two wives and nine children (one wife is heavy into another pregnancy) does not suggest “enlightenment”. The children are spaced by not more than a year.

“We hold workshops from time to time with them,” continued Chief Chapoto, “and the family you saw was because they are using modern methods of contraception, otherwise without any, that family would have been bigger than that.”

For his part, Stobart simply giggled away when asked how and why he has such a big family, under such circumstances as his. Of the nine children, most of whom are of school-going age, only three attend school, “because I cannot afford the fees to have them in school”.

Another characteristic of the Doma people is their shyness as they don’t look you straight in the eye.

“That is one way of telling whether someone is a Doma or not,” explained Jabesi, “they don’t look you in the eye. When you are talking to them, they stare at the ground. No-one has been able to explain this behaviour.”

But if the Doma people have any catching up to do, it all has to do with their methods of farming. With the river drying up at the end of the rainy season, around end of May or in early June, they start planting their maize in the river bed. All things being equal, this crop reaches harvest time without any rain and uses the humus of the river bed for fertility. The maize crop will be a healthy harvest that is if you take away the hippo, buffalo, elephant and baboon equation, for these animals easily find a ready crop to feast on. The need to guard the crop against these animals mean that fathers and mothers have to leave their homesteads for the river basin where they have to be on guard round-the-clock.

The maize crop will be a healthy harvest that is if you take away the hippo, buffalo, elephant and baboon equation, for these animals easily find a ready crop to feast on. The need to guard the crop against these animals mean that fathers and mothers have to leave their homesteads for the river basin where they have to be on guard round-the-clock.

“We left home in June and we are still guarding our fields from the wild animals,” explained Tamburai Chinobaiwa, “and we will be going back home just after the onset of the rains.”

Going back soon after the rains will, in a way, be running away from the flood waters.

“But what makes their farming methods improper,” further explained Jabesi, “is that they don’t get to have any meaningful yield from their crops because the cob that gets ripe is roasted there and then. Or boiled.”

Right at the top of the hill, in a section of the village commonly referred to as Chinhoi, is where Chinobaiwa’s family resides. He is father to six children, three boys and three girls. And of the girls, two of them got the autosomal condition from their paternal grandfather.

“My father had the same condition but in our family of five, born to my father, none of us had the condition. And in my family of six, two girls have had the condition. Their behaviour and interaction with other children from the community is normal and we have never had any problem, like our children complaining that they had been mistreated or misjudged because of their condition.”

Source: sundaymail.co.zw