The Falkland Islands may at some point in the future face a major tsunami.

Scientists have found evidence of ancient slope failures on the seafloor to the south of the British Overseas Territory.

Computer models suggest these underwater landslides would have been capable of sending waves crashing on to the Falklands’ coastline that were tens of metres high.

Fortunately, such events only appear to happen once every million years or so.

That means islanders shouldn’t stay awake at night worrying about them, says Dr Uisdean Nicholson who’s been investigating the issue.

“But you do want to capture risks at a range of different timescales. So I definitely think we should do more research to understand the different ways these events might be triggered,” the Heriot-Watt University geologist told BBC News.

The submarine landslides all occurred in the same location – on steeply inclined terrain on the edge of a raised region of the seafloor known as Burdwood Bank.

Seismic data reveals examples of repeat sediment failure where mud, sand and silt has tumbled down-slope into deeper waters.

The volume of material involved for the larger events appears to be around 100 cubic km.

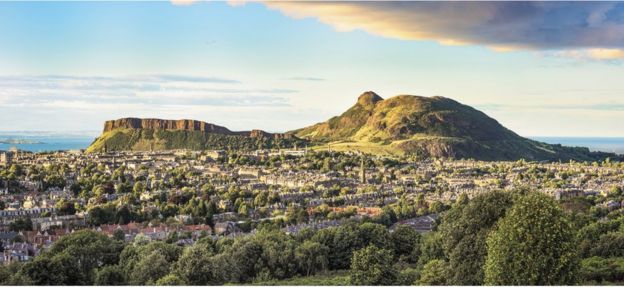

“That’s approximately the same as if you were to cover the whole area of Edinburgh, right out to the bypass, with 400m of sediment. You would cover Arthur’s Seat,” the Scottish scientist explained.

Nearby exploratory drilling by oil companies and scientific expeditions has allowed the team, which includes the British Geological Survey (BGS) and University College London, to roughly date the sediments and constrain the frequency of the slope failures.

Three or four of the “Edinburgh-sized” slides have occurred in the last three million years.

Everyone knows now that certain types of giant earthquake will trigger ocean tsunami by pushing up or depressing the column of water directly above a rupture in the seafloor.

Less well recognised is that sudden slumping of sediment in underwater landslides will achieve the same effect.

A recent example includes the September 2018 event at the Indonesian island of Sulawesi where a quake set off a number of submarine slope failures that then directed two-metre high waves at the city of Palu.

And in 1998, a submarine landslide sent 15m-high waves on to Papua New Guinea that killed 2,200 people.

Landslide-induced waves can be very big indeed, especially close to the source – although their energy tends to fall off quickly with distance.

The Falklands are about 150km from Burdwood Bank. Even so, the modelling suggests the larger slope failures could produce waves as high as 40m on the territory’s southern shoreline, and perhaps as tall as 10m at the capital, Port Stanley.

“We must stress these are old events that we’ve looked at; we don’t want to put the fear of God into people,” said BGS Prof Dave Tappin. “But the more events and case histories we study – even if they are millions of years old or a hundred thousand years old – the better we can understand not only how such tsunami are generated but also their likely future hazard.”