Data sent back by the two Voyager spacecraft have shed new light on the structure of the Solar System.

Forty-two years after they were launched, the spacecraft are still going strong and exploring the outer reaches of our cosmic neighbourhood.

By analysing data sent back by the probes, scientists have worked out the shape of the vast magnetic bubble that surrounds the Sun.

The two spacecraft are now more than 10 billion miles from Earth.

Researchers detail their findings in six separate studies published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

“We had no good quantitative idea how big this bubble is that the Sun creates around itself with its solar wind – ionised plasma that’s speeding away from the Sun radially in all directions,” said Ed Stone, the longstanding project scientist for the missions.

“We certainly didn’t know that the spacecraft could live long enough to reach the edge and leave the bubble to enter interstellar space.”

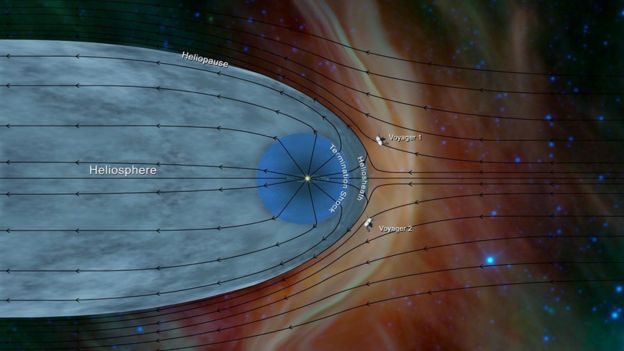

The plasma consists of charged particles and gas that permeate space on both sides of the magnetic bubble, known as the heliosphere.

Measurements show that the identical probes have exited the heliosphere and entered interstellar space – the region between stars. Voyager 1 entered interstellar space in 2012, Voyager 2 crossed over late last year. The key sign in both cases was a jump in the density of plasma.

This showed that the spacecraft were passing from an environment with hot, lower density plasma characteristic of the solar wind and entering a region with the cool, higher density plasma thought to be found in interstellar space.

The boundary between the two regions is known as the heliopause.

“We saw the plasma density at the heliopause jump by a very large amount – a factor of 20, at this rather sharp boundary out there,” said Prof Don Gurnett, from the University of Iowa.

“Actually, with Voyager One we saw an even bigger jump.”

The findings suggest that the heliosphere is symmetrical, at least at the two points that the Voyager spacecraft crossed. The researchers say these points are almost at the same distance from the Sun, indicating a spherical front to the bubble – “like a blunt bullet”, according to Prof Gurnett.

The results also provide clues to the the thickness of the “heliosheath”, the outer region of the magnetic bubble. This is the point where the solar wind piles up against the approaching wind of particles in interstellar space, which Prof Gurnett likens to the effect of a snow plow on a city street.

The heliosheath appears to vary in its thickness. This is based on data showing that Voyager 1 had to travel further than its twin to reach the heliopause, where the solar wind and the interstellar wind are in balance.

Some had thought Voyager 2 would make that crossing into interstellar space first, based on models of the magnetic bubble.

“In a historical sense, the old idea that the solar wind will just be gradually whittled away as you go further into interstellar space is simply not true,” says Don Gurnett.

“We show with Voyager 2 – and previously with Voyager 1 – that there’s a distinct boundary out there. It’s just astonishing how fluids, including plasmas, form boundaries.”